Last Thursday, we hosted a webinar with Ellen Stolzenberg and Jennifer Berdan Lozano from UCLA’s Higher Education Research Institute (HERI) to talk about the results of their 2014 Faculty Survey, a comprehensive research instrument for the professoriate in the U.S. The survey is designed, among other things, to identify sources of faculty satisfaction and stress, assess research and service activities, and examine how faculty define their roles. Because we’re particularly interested in service—how much time it takes, how faculty feel about it, and whether there is equity across faculty groups—we spent a lot of time discussing their findings in this area, but we also touched on the big picture of faculty work with survey results about research and teaching as well.

Good news! When it comes to service, most faculty feel that service is important and most agree that it’s valued, although the alignment between faculty about service stops there. For instance, non-tenure track faculty feel less valued than their tenure-track peers (only 40.4% feel strongly that their service is valued compared to 46.8% of tenure-track faculty). When you start to look at STEM/non-STEM, the gap is even wider between the perception of value around service performed by tenured or non-tenure track faculty.

Similar divisions can be found in a gender breakdown of the data, as well. Women are far more likely to place high importance on service than their male colleagues. Dr. Stolzenberg expressed a lack of surprise at these findings; she noted that existing research shows women demonstrate high engagement in volunteer activities outside of academia, too. The parallel between volunteer activities and professional service isn’t exact, of course, but they fill similar blocks in a scholar’s work week.

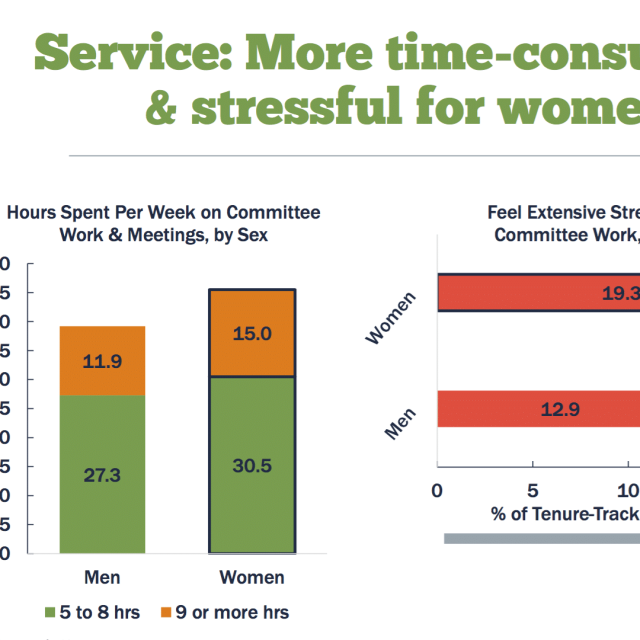

Unsurprisingly, then, women also report spending more time around service than their male colleagues, a phenomenon that’s been dubbed the “ivory ceiling of service work.” A full 15% of women spend nine or more hours per week on committees and meetings; only about 11.9% of men spend that much time. Least surprisingly of all, considering the above two findings, women feel more stress around service: 19.3% report feeling extensive stress about service, compared to only 12.9% of men.

Rank has a part to play, as well. Among tenure-track faculty, associate professors spend more time on service than their colleagues who are assistant and full professors. They also feel the most stress from their service work. These findings seems in line with research on the “midcareer slump” of associate professors, a scenario caused in part by increased service obligations. Why? Associate professors often find themselves protecting the time of junior colleagues still in the race for tenure (and possibly covering for senior faculty who are, for any number of reasons, less engaged in institutional service work).

Although associate professors spend the most time and feel the most stress about service, there’s no direct correlation between hours spent and stress. For instance, assistant professors spend less time than both full and associate professors on service, but feel very stressed (15.9% report feeling “extensive stress,” while only 14.1% of full professors make that same claim). In fact, service tends to be stressful no matter how much time you spend: of those tenure-track faculty who said service was an “extensive” source of stress above only about a third spent over 9 hours a week on service; the other two thirds of highly service-stressed faculty were split evenly between spending 1-4 and 5-8 hours per week on service. It seems like stress, if you perceive it, isn’t necessarily the result of how long you’re sitting around the committee table.

Perhaps least surprising of all, part-time faculty spend little time on service: 70.6% spend none at all, and about a quarter spend between 1-4 hours per week. This is likely a result of what has been reported as an institutional failure to include contingent faculty in professionalization activities, which includes meetings and governance activities.

The interesting part about research of this nature—that is to say, statistically significant, nationally representative, and highly specific—is that although in many ways definitive, it often suggests more questions than it resolves. It’s fascinating to know that women spend more time on service, but why? And, if non-tenure track faculty feel less valued, how can institutions help? Of course, if HERI’s mission is to stimulate change by providing information, then it make sense: institutions work with HERI so that they can draw their own conclusions about why these issues are happening, what policies might cause or solve them, and how they can best affect change.

For folks who are interested, here’s a deeper peek into the demographics of the study: It’s been administered every three years since 1989 to over half a million faculty at over 1,100 two-and four-year colleges. [In fact: registration for the next survey is open now!] From the 2013-2014 survey, HERI is able to create a nationally normative profile of over 16,000 full-time undergraduate faculty from 269 four-year colleges and universities. Because of the growing trend to hire part-time contingent faculty, they also provide unweighted data from over 3000 part-time faculty at 171 four-year colleges, as well. (The institutions they work with decide which faculty groups to survey on their campus). A bit more detail on who makes up the “faculty” of this survey: of the full-time group, 78% are tenure track and 22% are non-tenure track. 58.1% were men and 41.9% were women; 83.4% were white, and 16.6% were faculty of color. The majority of respondents (63.9%) were in non-STEM fields.