This post continues our series, The Smart Scholar, with a focus on preparing for life on sabbatical.

In a previous post, I provided three tips for candidates working with search firms. After the release of that post, myself and Interfolio staff received several comments and questions from readers about job-seeking advice and the role search firms can play in securing future employment. Given these questions, I reached out to search firm representatives to understand, from their subject-matter-expert perspective, tips and strategies for candidates.

I solicited the advice of Dr. Sherry Coleman, Consulting Partner with Storbeck Search and Associates and Ms. Maya Kirkhope, Senior Consultant with Academic Search. To help organize the advice provided from both experts, below I summarize insights from our interviews on how to get on a search firm’s candidate database, prepare and review required applicant documents, and engage in the phone/video interview.

Getting on the search firm’s candidate database

During my conversations with Dr. Coleman and Ms. Kirkhope, both suggested that candidates often get on their radar through:

- Their 1:1 conversations with professionals in the field (e.g., other search firms, higher education professions)

- Their targeted research efforts

- Through candidates’ own efforts, such as reaching out directly to search firm representatives

Both experts encouraged candidates to reach out to search firms. Dr. Coleman suggested that it is important for candidates to reach out to search firms to:

“… create a plan of action… and see what’s available, what’s out there, what are search consultants looking for, what are the organizations they represent looking for so that they can better prepare themselves for the search that is of interest to them.”

Ms. Kirkhope shared similar advice to Dr. Coleman and advised candidates to reach out to search consultants because:

“I think the advice and the guidance that we can offer can be incredibly helpful. Sometimes it’s not what you want to hear. Sometimes it’s about the readiness to get onto the market. Sometimes it’s really whether the skill set that we’re looking for for this position is going to be a good match.”

Mrs. Kirkhope explained that it was important as a consultant to help inform candidates if they had the prerequisite experiences—that would make them a viable candidate for a position—before they apply.

Through our conversations about how to get on the search firm’s radar, I found that it is equally important for candidates to research search firms.These agencies are businesses and they each have their own niche of search they typically engage in. For instance, some firms only conduct searches for senior administrative positions (e.g., President, Provost), where other firms also recruit for endowed professorships.

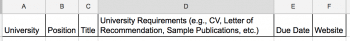

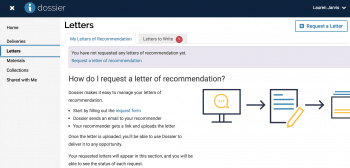

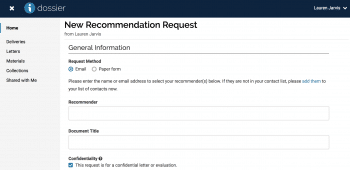

Preparation and review of applicant documents

From my experience serving on faculty searches, candidates may lack in presenting carefully crafted written materials. This is often a part in the process that can quickly eliminate a candidate from consideration for positions. During my conversations with the experts, they too expressed the importance of candidates putting together strong materials. Ms. Kirkhope expressed that common mistakes with applicant materials include:

- The candidate’s CV is too long and is not tailored directly to the position the candidate is applying for. This signals to the committee that you may not understand what the search committee is searching for, specifically to determine if a candidate is a fit for the position.

- The selection of references are not adequate for the position (e.g., you apply for a leadership role and have no reference that can speak to your formal leadership experience).

- The cover letter does not address how the candidate’s experience meets the qualifications of the position.

In a follow-up interview, Mrs. Kirkhope suggested that when preparing materials, a candidate could give a summary overview of areas on their CV that were not directly related to the position such as listing a sample of classes taught when applying for an cabinet-level administrator role.

Dr. Coleman also explained that when creating a cover letter, candidates should make sure it is tailored to the job position and institution to which they are applying. She explained, “So you want to make sure your materials reflect your strengths, your experiences, your ability and is it your cover letter may address some of your least experienced areas. You want to make sure that your references complete your story.”

My takeaway on job material preparation? Take the time upfront in crafting your cover letter and selecting your references. Your goal for your written materials is to have the search committee eager to learn more about you and how you are a fit for the position. In many cases, this will lead to a video interview.

Thriving on the video interview

A question many readers from my previous post asked was, “How do I prepare for the video interview?” So, I had an extensive discussion with Dr. Coleman and Ms. Kirkhope about how candidates should prepare for this event.

Dr. Coleman suggested some very poignant steps candidates can take to succeed during the video interview:

“Well I think some people are not comfortable with sort of video conversations and I would say practice from every aspect. Where you’ll be seated, what’s in the background, how high your laptop computer is so that you present well, are there glares? If you have glasses, is there glare on your glasses? And some of that has to do with positioning. And so you want to practice that ahead on Zoom with a friend or colleague or someone who can give you feedback.”

Dr. Coleman added that search firm consultants could possibly be helpful in giving candidates suggestions for the types of questions they will be asked. She also advised that whenever possible, candidates should reach out to colleagues who hold the position they are applying to in order to understand the types of questions they should be prepared to answer.

Ms. Kirkhope added to Dr. Coleman’s recommendations on interview preparation by encouraging candidates to make sure they are actually answering the search committee’s questions.

“A lot of times people think they are answering,” Ms. Kirkhope explained, “but one of the biggest mistakes candidates make is they get very general in their responses. They don’t provide examples, or they talk incessantly and they spend 20 minutes on the first question. When interviewing you typically have 4-5 minutes per question.”

She further explained that not answering all of the questions impacts candidates at decision time. Search committees may not have candidate responses to key areas that are germane to their position, thus they may be less likely to move forward in the search.

My takeaways? When thinking about a video or in-person interview, candidates should prepare ahead of time, solicit the feedback of a trusted colleague, and think intentionally about specific examples that allow you to thoroughly answer a question.

What thoughts come to you after reading this post? Are there any lingering questions about working with search firms? Feel free to reach out to me on Twitter.

I would like to personally thank Dr. Coleman and Ms. Kirkhope for their time in serving as experts for this piece.

Author Bio: Dr. Ramon B. Goings is an assistant professor of educational leadership at Loyola University Maryland. His research examines gifted/high-achieving Black male academic success PreK-PhD, diversifying the teacher and school leader workforce, and the student experience and contributions of historically Black colleges and universities to the higher education landscape. Dr. Goings is also the founder of The Done Dissertation Coaching Program which provides individual and group dissertation coaching for doctoral students. For more information about Dr. Goings’ research please visit his website www.ramongoings.com and follow him on Twitter (@ramongoings) and for more information about The Done Dissertation Coaching Program visit www.thedonedissertation.com.

Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of Interfolio.