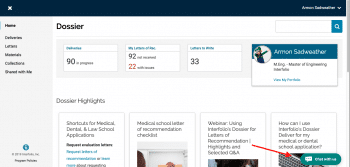

Interfolio’s Dossier began in 1999, and back then, our delivery structure of sending materials to an opportunity was pretty straightforward. We originally only processed deliveries via USPS, FedEx, fax, and a few by email. Our main clients were faculty members or those applying to faculty roles. We continue to serve scholars seeking tenure-track faculty positions, but our online products now serve people in a much wider range of situations, including medical school applicants, graduate students, social workers, surgeons, and even several football coaches.

At the core, our mission has stayed the same: Putting our users first by providing them with consistent tools for their careers. To a significant degree, Dossier Deliver exists to deliver materials to jobs, grants, fellowships, medical school programs, grad school, etc.

Here, we explore the various types of deliveries, including the intricacies of each type.

Email Delivery

What is it? Use this when you want Interfolio to send your materials directly to an email address.

Sometimes, a search will want materials to be sent to a specific individual instead of a group email address. For example, “You can send your materials/application to me at firstname.lastname@school.edu.”

Other times, a search wants those materials to be sent to an HR or department address. For example, “Apply to this position by emailing your LORs & CV to hr@school.edu.”

Either way, when creating your delivery through your Dossier account, you’ll need to provide us with the name of the recipient and the correct email address.

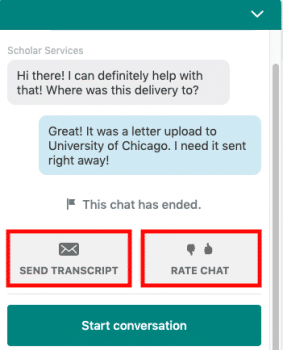

Issues With Your Delivery?

- Was your delivery canceled? If so, reach out to us, and we’ll be happy to explain why that happened.

- If we are not able to verify the email address, you can forward us proof of a conversation with that individual that explains they are expecting materials from you.

- Or you can provide us with a URL that includes the email address where those materials need to be sent. You can do this during the delivery creation process.

- If you have received confirmation from us that your delivery was sent but your delivery recipient has not received the email, the first step is for the delivery recipient to check their spam folder. If it’s not there, reach out to us and let us know. We’ll be able to resend the delivery to help ensure it gets to the intended recipient without any problems.

Tips & Tricks

- You can include as many documents as you want in an email delivery. So, if you’re looking to send many documents that are hundreds of pages long, we encourage using the email delivery option.

- You can “order” the materials in your email delivery, meaning you have the ability to arrange them in a sequence of your choosing. This allows them to be read in a certain order by the intended receiver. You can do this during the delivery creation process.

Mail Delivery

What is it? Use this when you want Interfolio to mail physical copies of your materials to a destination. Please note that different institutions have different requirements.

Issues With Your Delivery?

- Was your delivery canceled? If so, reach out to us, and we’ll be happy to explain why that happened.

- If we were not able to verify the address, you can forward us proof of a conversation with that individual that explains they are expecting materials from you.

- Or you can provide us with a URL that includes the address where those materials need to be sent.

Tips & Tricks

- There are a number of shipping methods to choose from. Included in your Dossier Deliver subscription is the “USPS First Class” option—there is no additional cost to you for this shipping option. All other options have an additional cost associated with them. This is a good reason to stay on top of deadlines so you can avoid rush delivery and the additional cost.

- If you want tracking for your mail delivery, sending FedEx is the only option. FedEx deliveries have an additional cost.

- You can “order” the materials in your mail delivery, meaning you have the ability to arrange them in a sequence of your choosing. This allows them to be read in a certain order by the intended receiver. You can do this during the delivery creation process.

- Please note that we are unable to deliver to P.O. Boxes.

Confidential Letter Upload (CLU)

What is it? The trickiest of the bunch! Use this when you want Interfolio to upload your confidential letters of recommendation into another online application system. This option is most commonly used by medical school applicants.

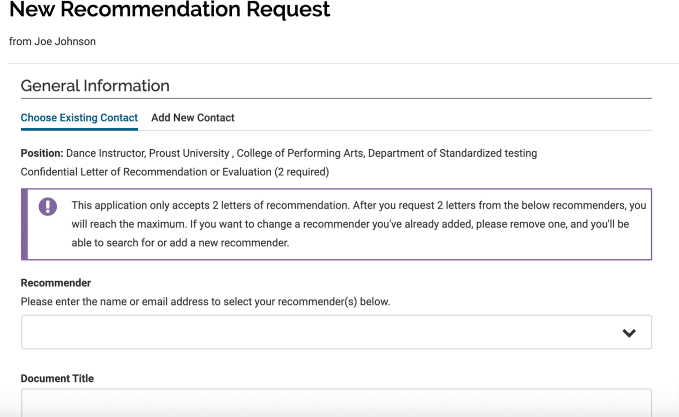

This type of delivery takes one of two forms: either the external system provides you with a link to pass along to your letter writers or the external system asks you for your letter writers’ email addresses.

When the external system provides you with a link to pass along to your letter writers:

In this situation, you simply follow the Confidential Letter Upload instructions when creating a new delivery in your account. You paste in the upload link and indicate which letter you’d like us to upload, and we go and upload it there. Simple!

When the external system asks you for your letter writer’s email address:

In this situation, Interfolio can substitute for your letter writer. (Except sometimes, unfortunately, when we can’t. See below for exceptions.)

Suppose you are applying to Demo University and have been asked to provide them with the email addresses of three letter writers. Normally, the school would reach out to your letter writers via those email addresses, asking them to upload a letter of recommendation. If you have letters stored in your Interfolio Dossier account, Interfolio can often stand in for your letter writer and upload letters on their behalf.

In order for Interfolio to process these deliveries, we automatically generate a unique email address associated with each letter of recommendation you have in your Dossier account. When the external online application system asks for your letter writer’s email address, you can substitute the unique Interfolio email address associated with that writer’s letter. Once you submit that request, you’re all done—we’ll take care of the rest.

Issues With Your Delivery?

- We may have to cancel a delivery due to required questions within the application that we do not know the answers to. Unfortunately, if we run into questions that must be answered on behalf of your letter writer to upload the letter, we cannot legally do this. Some possible personal questions that prevent us from processing the delivery include:

- Rank the applicant among other students in recent years

- How long have you known the applicant?

- How well do you know the applicant?

- We also cannot complete a delivery when a user is prompted to upload the letter of recommendation themselves. In these situations, users will provide us with their login information to upload the letter. We cannot accept that information from the user—it’s a liability for us to have that information.

- If confidential letter uploads are ever canceled, we suggest you reach out to the institution directly and explain why. They can often provide you with an email address to send materials directly, then they can upload the letters to your application. (See email delivery above!)

Tips & Tricks

- Make sure you are submitting the document email address found in your Dossier account when the application asks for your letter writer’s email address and be sure to submit that request. Going through the CLU delivery process via the Delivery page on your account alone does not create the requests—you must make sure you are entering in that information and submitting it on the application website.

- Haven’t received confirmation that we’ve received the request? Give it a little time. We do receive requests instantly. Unfortunately, we have no control over when the application sends the request to the document email address you entered. If you think it’s been an appropriate amount of time since you submitted that request and you still haven’t received confirmation that we’re working on the delivery, reach out to us, and we’ll double-check to see if we’ve received the request or not.

- Need to submit your application before you’ve received the letter in your account? Contact us and we can give you the unique email address to enter your application.

- Our one to three-day turnaround time is once we receive the request, not once you submit the request on the application. Sometimes there is a delay from when you submit the application/request and when we receive it.

Running up against a deadline? As always, we can expedite most delivery types for you. Just send an email to help@interfolio.com with your delivery number letting us know you need it expedited, and we will get to work on that ASAP.

In 2023, we processed 218,719 Dossier Deliveries for our users. Trust Interfolio with yours.

Interfolio’s Dossier enables scholars to collect, curate, polish and send out their materials at all stages throughout their academic professional path. Learn more about Dossier here.