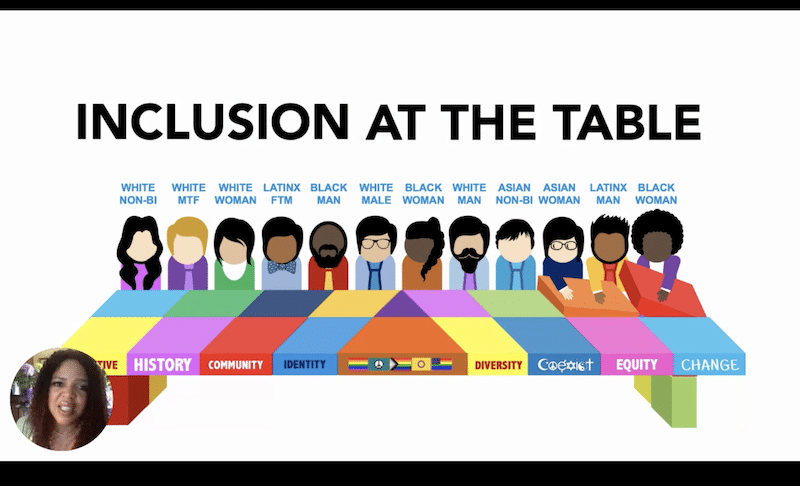

A diverse faculty body brings a range of experiences and backgrounds to their roles as educators and researchers; they represent multiple races, ethnicities, genders, ages, sexual orientations, and abilities, and they exhibit unique scholarly interests, viewpoints, and teaching and learning styles.

Faculty diversity has been shown to positively affect student outcomes, including increasing retention and graduation rates. To best serve student needs, an institution’s faculty should reflect the student population, from race and gender to sexual orientation. But according to data from the American Council on Education (ACE), over one-third of higher education students are Black, Latinx, or Native American—and only 11% of faculty reflect those populations. As of 2018, roughly 76% of faculty at postsecondary institutions were white.

As student bodies become more diverse, many colleges and universities recognize the importance of improving faculty diversity and have put robust plans in place around diversity, equity, and inclusion—but how many are realizing their goals?

The Benefits of a Diverse Faculty

Research shows that faculty diversity in higher education supports the success of students from underrepresented groups as well as all students’ intercultural competence.

The positive effects of a diverse faculty are clear:

- In institutions where a majority of faculty are white, students of color may see Black and Latinx professors as role models or mentors, increasing their sense of belonging.

- Female students report feeling like they receive more help and support from female faculty.

- Black students in STEM courses taught by Black instructors are more likely to stick with STEM after their first year.

- Faculty diversity can also lead to a greater variety of scholarship and research, expanding societal knowledge and understanding.

While the benefits are apparent, institutions are still struggling with recruiting, hiring, and retaining diverse faculty members.

How to Increase Faculty Diversity in Higher Education

ACE points to three areas of focus for institutions seeking to improve faculty diversity: 1) attractiveness of faculty positions; 2) hiring, tenure, and promotion processes; and 3) departmental and campus climates for faculty of color.

To meet these objectives, it is key that institutions ensure campus-wide commitment to diversity efforts, improve hiring practices, and support the success of faculty from underrepresented groups.

Ensuring Campus-Wide Commitment to Faculty Diversity

While making faculty diversity a priority is an essential first step, in order to effect lasting change, higher education administrators and department chairs should weave their institution’s commitment to faculty diversity into strategic plans and mission statements, as well as institutional policies.

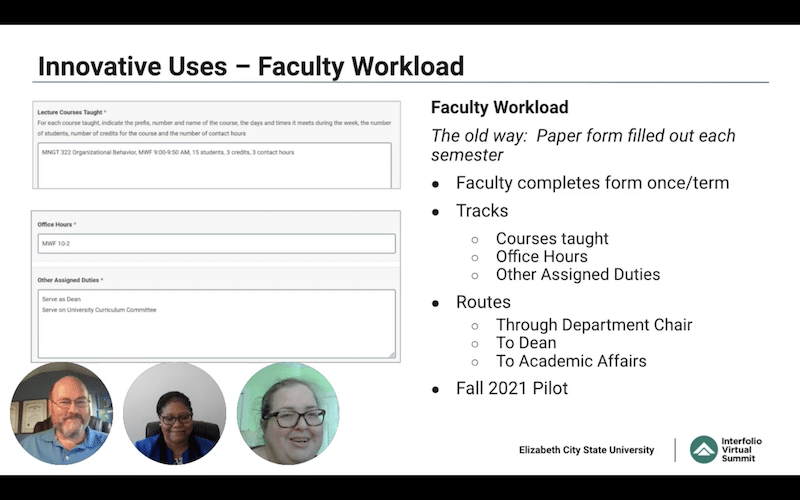

For example, institutional policies relating to faculty workloads and faculty review, promotion, and tenure need to be reexamined in light of how they impact faculty diversity. Institutions may need to adjust these policies to better support the retention of underrepresented groups and promote equitable faculty workloads.

To keep diversity goals top of mind, administrators should also remind community members of their institution’s diversity goals by reaffirming them during campus talks and meetings—and by making them part of any long-term strategy discussion.

Another essential part of realizing this commitment to faculty diversity is making specific changes to hiring practices.

Five Hiring Practices to Increase Faculty Diversity

Faculty affairs administrators and departments can actualize their institution’s faculty diversity goals by taking five important steps in faculty hiring:

1. Set department-based goals for diversity and inclusion

The first step each department should take is to discuss long-term goals related to faculty diversity and inclusion in hiring. This involves assessing past successes and failures to inform practices going forward and determining ways that faculty recruitment and selection processes can be more inclusive.

For example, for business schools that lack faculty from underrepresented groups, departments might discuss dropping the requirement of a Ph.D. for tenure-track candidates and instead consider candidates based on their business experience or possession of an MBA.

2. Elect an inclusive search committee

Gather search committees for open positions that include faculty from underrepresented groups that you hope to reach. If you struggle to find those members within your department, reach out to other departments to achieve an inclusive search committee.

3. Develop a broad recruitment plan

The hiring manager and search committee for any open position should develop a plan focused on attracting a large and diverse pool of applicants. This should include identifying resources that ensure the wide distribution of the position announcement.

Search committees can’t simply place an ad and sit back; they must actively seek out diverse candidates by tapping into professional networks and industry organizations to increase their reach. Committee members should also seek out specific organizations, websites, and publications that specialize in recruiting diverse faculty members.

UC Davis’s ADVANCE initiative, which seeks to increase the number of women in STEM careers, recommends that hiring committees take advantage of industry listservs, email groups, and registries. UNC Charlotte’s similar ADVANCE program also offers a list of resources for finding underrepresented faculty candidates.

4. Create an inclusive job listing

The job advertisement should clearly indicate your institution’s commitment to equity and diversity. Research shows that this practice is more likely to result in the hiring of a candidate from an underrepresented group.

In addition, define the position in the broadest possible terms consistent with the department’s needs. Try not to rely on overly narrow experience requirements and instead indicate your openness to non-traditional career experiences and pathways. For example, if you are hiring a professor of public policy, you might note in the posting that you are open to candidates with extensive public policy experience and that you do not require a master’s degree or Ph.D.

Ensure job announcements reach a broad audience by including outlets such as minority-serving publications, listservs, bulletin boards, and blogs. For example, you will likely want to post on the DiversityTrio job boards, which receive high traffic from faculty candidates from diverse backgrounds.

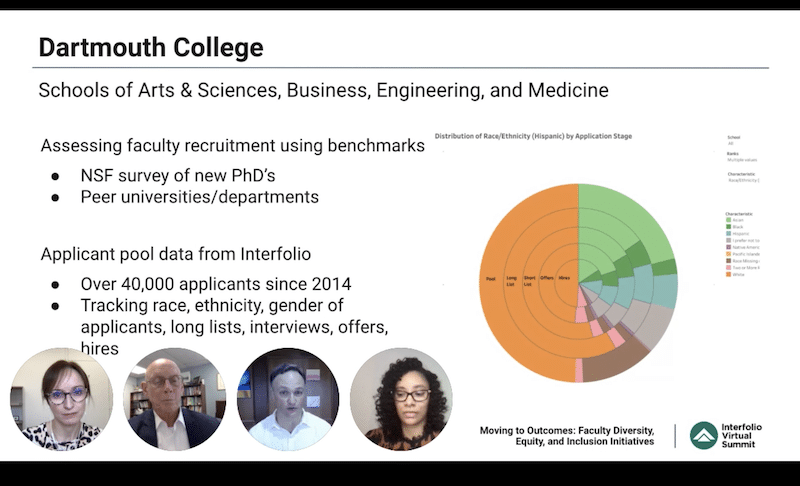

5. Monitor the recruitment plan

Once the hiring plan has been implemented, it’s critical that you monitor the diversity of the candidate pool while the submission window is open, not after. Committees should be able to monitor applicant data in real time so they can increase efforts to attract candidates from underrepresented groups and ensure the institution’s diversity goals stay on track.

Supporting Faculty Members From Underrepresented Groups

To attract and retain a diverse faculty, an institution must provide an appealing, supportive, and beneficial environment for scholars from underrepresented groups.

Look at your institutional policies relating to faculty workloads and promotion; in many instances, the distribution of labor may not be equal for women and faculty members of color. Invisible labor often doesn’t lead to promotion or tenure, and it can cause faculty to burn out and leave the institution entirely. It’s essential to take note of these inequities and create an inclusive culture with practices that support faculty members from underrepresented groups. Detailed faculty data reporting can make it easier to spot these inequities and track each professor’s workload and path to promotion or tenure.

Another way to support faculty is by creating mentorship programs dedicated to underrepresented groups or specific departments. For example, Black faculty in predominantly white schools may feel disconnected—both from each other and the institution as a whole. An institution can better encourage the success of its Black faculty by establishing communities where they feel welcome and valued.

Your institution may also want to pursue discussions and relationships with local and national minority organizations and other associations that focus on strategies for supporting faculty members from underrepresented groups. These organizations could include the American Association of Blacks in Higher Education, the National Center for Faculty Development and Diversity, and the Association on Higher Education and Disability.

Digital Tools to Help You Deliver on Faculty Diversity

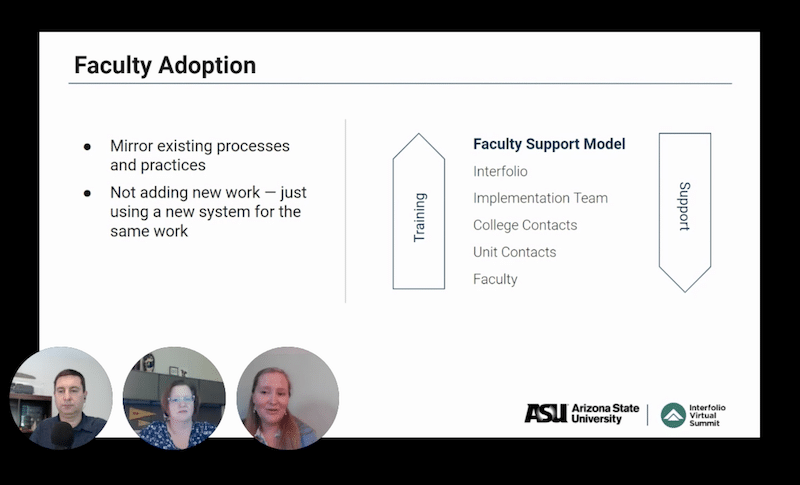

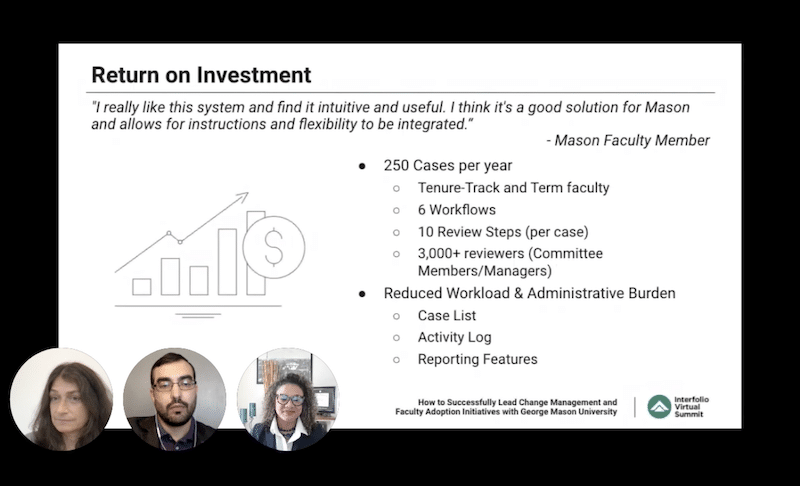

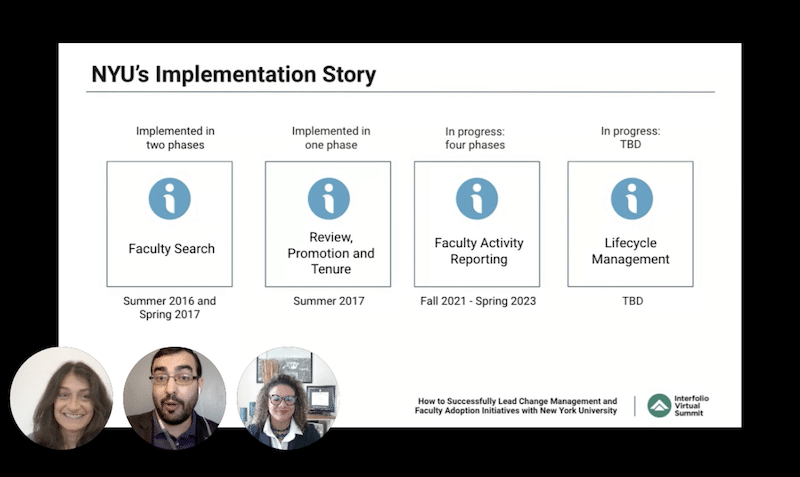

The Interfolio Faculty Information System can support your efforts to increase faculty diversity at every stage of the hiring process and beyond.

Trying to recruit a diverse pool of candidates? Faculty Search enables you to assess your applications during the submission window and intervene if the pool is not diverse enough using real-time, self-reported, anonymous demographic survey responses from 100% of applicants.

In addition, if your search committee has devised specific evaluation criteria, such as whether candidates offer real-world experience, Faculty Search enables you to make that custom criteria part of your digital workflow.

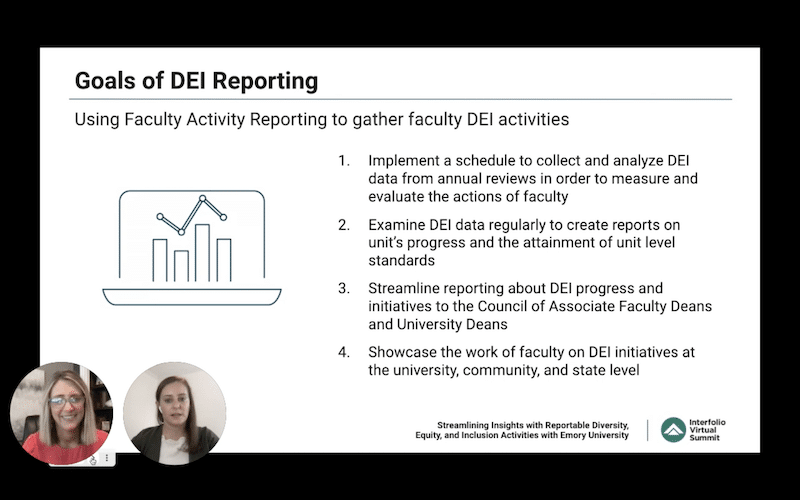

As you hire more faculty members from underrepresented groups, Interfolio’s Review, Promotion & Tenure software can help you support them using a documented review process that increases consistency and transparency. In addition, Interfolio’s Faculty Activity Reporting module makes it easy for faculty to document activities relating to student support, service, and diversity.

Need Additional Help?

Download Interfolio’s Best Practices Checklist: Achieving Diversity Across the Academic Lifecycle to see whether you’ve adopted the best strategies for recruiting and retaining diverse faculty candidates.